2025 UPDATE: My Celtic patterns can now be found in my online shop.

My first book Celtic Quilts: A New Look for Ancient Designs was published in 2000 by Martingale & Co.

The following has been excerpted from a lecture/trunk show that I have shared with quilt guilds, quilt show attendees, and various community groups around the country.

I’d like to share with you some of the things in my life that led to my becoming a quiltmaker, and ultimately to the writing of my Celtic book. I’m also going to try to answer some of the questions I’m asked most often. So please be patient with me – we are going to tiptoe down what might seem to be a couple of rabbit trails; but I promise that they do, in fact, bring us back to where we want to be.

It is my hope that even if you don’t have any interest whatsoever in Celtic designs (how could that be??) Or if you never even look at any of my books, we can find some common ground – it always amazes me how quilters can be so different from each other, and yet again still so much alike.

We make quilts because we love to. We need to. It’s not just about keeping warm – it’s about creativity, self-expression, comfort, healing (sometimes even grieving) and expressing love.

My own journey has encompassed all of these things.

As you will see, my quilts are not intended to be the ultimate in Celtic design. Instead, they are meant to reflect both my own heritage and my fascination with color and line. My book is meant to be a good starting point for anyone who is interested in making their own Celtic inspired quilts – especially those with limited time on their hands who would still like to achieve an heirloom look.

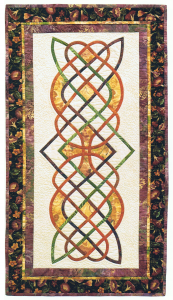

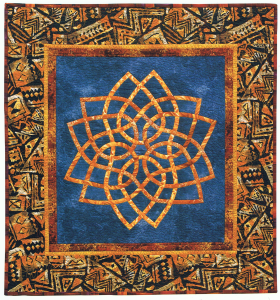

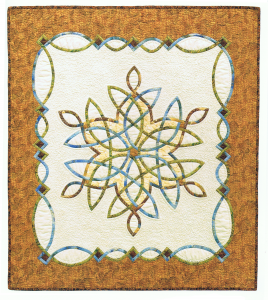

The quilts, table runner, pillows and wall hangings shown in this post are all from my Celtic Quilts book. Complete patterns for all but the final quilt shown are included in the book.

So, first of all, how and why did I begin using Celtic-style designs in my quilts?

This also relates to the question of why I began making quilts in the first place. There is a rich quiltmaking tradition in my family, (at the time I was growing up, almost every major milestone in life was marked with a quilt – birth, graduation, engagement, marriage, moving away, etc.). However, I did not begin making quilts in earnest – or sewing very much at all, for that matter–until after my youngest daughter was born.

I spent a good chunk of my growing-up years in various countries in Europe and Africa. During college, I returned to Africa, working as a translator. After marriage, my husband and I made plans to continue our training, expecting to dedicate ourselves to linguistic work in Africa – but this time together. But life doesn’t always turn out as we expect!

We never made it back to Africa.

Over the next five years, I experienced a series of life-threatening health crises that really destroyed my life as I knew it. I would stabilize, sometimes very briefly, and sometimes for months at a time, but then I would go back into a steep decline. At several points, it was very touch and go, and my long-term prognosis very uncertain. I was given one alarming diagnosis after another, and went through several operations. It was a very scary time for all of us.

I was ultimately diagnosed with a variant of MS, and with permanent heart, brain & nerve damage.

But we are often given special gifts of grace just when we need it most, and one of the gifts given me was a wonderful woman I came to call “Grandma” Baldwin. It was to her and to her daughter, Ada, that the Celtic book was dedicated – although sadly they both passed away before the book was released.

She had been a painter herself (among many other interests and abilities), and had also been involved in art therapy from the time wounded soldiers were returning from WW II. She knew how much I loved art, and also how much I needed to find a way to continue to be creative – a way to recognize myself – even with new and changing limitations. She was also prepared to lovingly “bully” me (if necessary) into getting started.

Grandma Baldwin told me about a wonderful quilting show then running on PBS, hosted by Penny McMorris, that talked not only about traditional quiltmaking, but also about quiltmaking as an expressive art form. I was hooked.

To be honest, I really didn’t need much persuading. By that time, I was already pretty much convinced that this was something I needed to do. Quilts made by my loved ones had always been a very comforting presence in my life – a tangible link between hearts beyond the confines of time and space. Given the uncertainty of my future, I was very afraid that my children, then just babies, would not remember be if I did not survive.

So, The first quilts I made were for my children. They were very simple, but the colors and shapes fit their personalities, and I was happy. I decided that maybe this was a good thing, and maybe I would explore this some more…. (and I’ll tell you right now that I’m not a good “dabbler”. I’m more of a “whatever thy hand finds to do, do it with thy might,” kind of person. We won’t mention words like “compulsive” or “obsessive,” thank you very much.)

At any rate, as I researched the history of quiltmaking, and became more aware of the many wonderful developments in contemporary quiltmaking, I began to realize that it was like a language, and if I could learn the “vocabulary,” I could continue to communicate. (At this point in time, my ability to process and respond to verbal speech had been profoundly disrupted; any who know me can imagine how devastating that was for me.)

I set a goal to research and learn as many techniques as I could – to visualize technique, design, and especially color as vocabulary – with the end goal of being able to design and create freely whatever I wished; being able to communicate images, ideas, emotions, etc. without worrying about the “how-to.”

John would bring back stacks of 10-20 books at a time home from the library, or to the hospital. When I could sew, I would. When my motor control was impaired, I read and researched.

Along the way, I also discovered that it was not only the product that was important to me, but also the process. The physical discipline of working through the stages of quiltmaking helped gradually lead to an acceptance of the changes in my life – and helped me to begin to visualize that this could become a viable new career path for me.

I began working on several series of quilts. As I worked, Grandma Baldwin was right there with me – my biggest supporter and occasional thorn in the flesh. She encouraged me to learn “the way things are done,” but also to see if I could figure out other ways that might be more practical or useful for me. She helped me to think of fabric as “paint,” and to make my purchases based on what “spoke” to me. Pretty progressive for a lady in her nineties!

The nudge into Celtic-style designs came from multiple sources. First of all, I was very aware of my family’s Celtic ancestry. (In fact, I may have been in my 20s before I realized that the Irish potato famine happened some 150 years ago. To hear my grandfather talk about it, you would have thought it had happened sometime last week.) I was interested in reflecting that heritage in at least some of my work, especially since so many of my other pieces so strongly reflect my experiences growing up overseas.

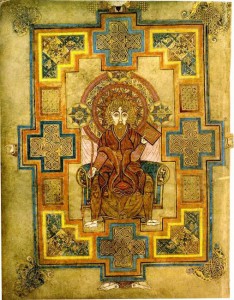

I also became aware of Philomena Durcan’s book of designs based on the book of Kells, and was intrigued by the concept of incorporating ancient Celtic designs, but was put off by all the hand work involved in her methods.

Although I’ve always enjoyed handwork, I continue to have intermittent paralysis and weakness, particularly on my left side, so I really do need to be able to do most of my work on my home sewing machine. This was a discouragement me to me at first, but I eventually realized that the machine stitching could also be another design element in my work – especially when I discovered free motion quilting and all the beautiful decorative threads available. Now I love the additional layer of texture and detail that machine quilting can provide.

So, naturally, being the enthusiatic person that I am, I immersed myself in my own study of ancient Celtic culture and began experimenting with my own techniques. When I first took my work into the public arena, it was as an Irish-American fiber artist, exploring and sharing part of my heritage; and as an art quilter, exhibiting both my Celtic and non-Celtic related work in area galleries and at regional cultural events.

Which brings us back to the Celts. Who were they?

I learned that the Celts, often called “The Fathers of Europe,” became identifiable as a distinct people group around the 8th century BC. At one time, Celtic peoples stretched across the face of Europe from Ireland to the Ukraine, and from what is now Spain to Asia Minor, rivaling the Roman Empire in scope and influence. Although there was never a “Celtic” empire, Classical Greek and Roman sources recognized individual tribes, such as the Gauls, the Iberians, and the Britons, as sharing commonalities of language, custom, and material culture. The Greeks and Romans referred to these tribes as “Keltoi,” “the hidden, or secret people;”or as barbarians, a term greatly misleading today. The Celts (generally pronounced Kelts) were a highly developed warrior society with rich oral traditions, sophisticated legal structures, and complex personal allegiances based on kinship. There were especially famous for their superb horsemanship and exquisite metalwork.

The Celts were noted for their love of decoration, and for the way they incorporated design and pattern into everyday life – lavishing detail on functional, everyday items, and not only on sacred or ceremonial objects. Beauty in form seems to have been just as highly valued as efficiency in function.

In their heyday, the Celts enjoyed great military success and renown. In the 3rd century BC, Celtic tribes sacked Rome, encountered Alexander the Great along the Danube, advanced into Greece, and pillaged Delphi. The Galatians addressed in St. Paul’s New Testament epistle were Celts. But while the Celts were effective colonizers, they had no centralized authority, and were unable to hold their conquests. The Roman invasion of Europe, ending with the conquest of Britain in the first century AD, sounded the beginning of the end for the Celtic way of life on the European continent. Although many Celts were absorbed into the indigenous populations, Celtic chiefs were no longer in control. Subsequent invasions of Celtic territories by various Germanic tribes, Norse Vikings, and (much later) the Normans continued the push westward. This lead to the formation of the what is now known as the “Celtic Fringe” on the western edge of Europe: Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Isle of Man, Cornwall in England, Brittany in France, and (arguably) Galicia in Spain. Today’s Celts trace their ancestry to these countries.

With the spread of Christianity in Ireland in the fifth and sixth centuries AD, Celtic culture was transformed once again; but this time the transition was peaceful, and lead to possibly the greatest flowering of Celtic art. The spirals, scrolls, compass-work, palmettes, foliage, tendrils, triskeles, zigzags, and simple geometric shapes of earlier Celtic cultural periods of Hallstatt and La Tene married with the animal interlace brought by the Germanic invaders of Britain, and the stylistic influence of Mediterranean Christianity, producing the style commonly recognized today as “Celtic.”

The patterns in my book are based on knotwork and interlace styles associated with this period.

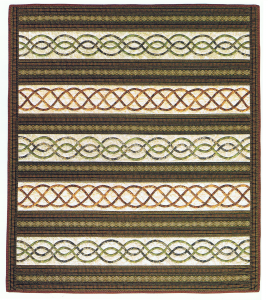

However, I am certainly not alone in using Celtic motifs in my quilts. Traditional Welsh whole-cloth quilts are recognized for their masterful use of spirals. For centuries, many quilts in Ireland, the British Isles, and North America have used Celtic-style cables and braids as quilting patterns.

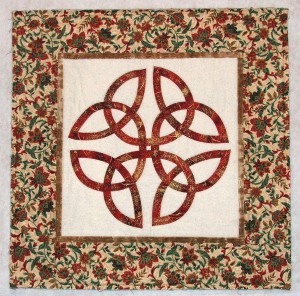

Another traditionally favored quilting pattern is the Celtic True Lover’s Knot, one version of which I include in the book as a beginner pattern.

This design is also effective on point:

What is the significance or symbolism of these designs?

Celtic art and design is used to support ethnic identity. It is also often used for the glorification and worship of God, continuing the tradition of the magnificent gospel manuscripts, standing crosses, reliquaries, and liturgical vessels of over a thousand years ago. Others use Celtic symbols to connect with pre-Christian traditions of spirituality. Finally, many people are drawn to Celtic designs simply because they are beautiful.

In my original Celtic-style patterns, (as well as in my interpretations of historical designs), I have remained true to three characteristics of “classic” Celtic knotwork and interlace:

- All lines are continuous, having neither beginning nor end.

- All lines cross each other in an alternating “under-over-under” pattern.

- No more than two lines cross at any given point.

The unbroken lines in Celtic knotwork were used to symbolize the pagan cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, as well as later Christian concepts such as the glorious and sometimes mysterious workings of creation, the unending qualities of God’s love and mercy towards us, and the eternal nature of the soul. The “endless knot” symbolically ties our souls to the world, or alternatively, to God.

A sense of motion, or the turning of the cosmic wheel, is a characteristic of much of Celtic art.

In addition to the marvelous metalwork and stonework the Celts left behind are the beautiful illuminated manuscripts created by monks in Ireland and the British Isles, and carried all over Europe and even into Asia by Irish missionary monks in the 7th – 9th centuries. A few of the most famous are the Book of Durrow, the Lindisfarne Gospels, and the Book of Kells.

Some of the designs in my book are adaptations of designs from these fantastically decorated gospel books.

Crosses are yet another a recurring element in both pre-Chistian and Christian Celtic knotwork.

What Is different about the designs and methods described in my book?

As I just noted, some of the designs are adapted directly from ancient sources; others are modern interpretations of Celtic forms; and still others are brand new designs rooted in Celtic style.

The methods used in this book combine traditional methods with new innovations such as

- cutting strips on the bias,

- folding and sewing each strip into a tube,

- using a pressing bar to center the seam allowance on the underside of the each bias tube,

- “basting” the bias tubes in place with pressure-sensitive adhesive (such as Steam-a-Seam 2) or water-soluble adhesive (such as Roxanne’s Glue Baste-It – my current favorite adhesive for appliqué)

- using monofilament thread to applique by machine with “invisible” stitches,

- machine quilting with various types of thread to add additional texture and interest.

Most of the projects also lend themselves to a quilt-and-appliqué-all-in-one step approach.

As an example of the versatility of these designs, consider these 3 quilts, all made from the same pattern:

I tried to keep the techniques in this book very practical, and as timesaving and streamlined as possible; so they could be accessible to people who may not have huge blocks of time to invest, but still wish to produce high quality results.

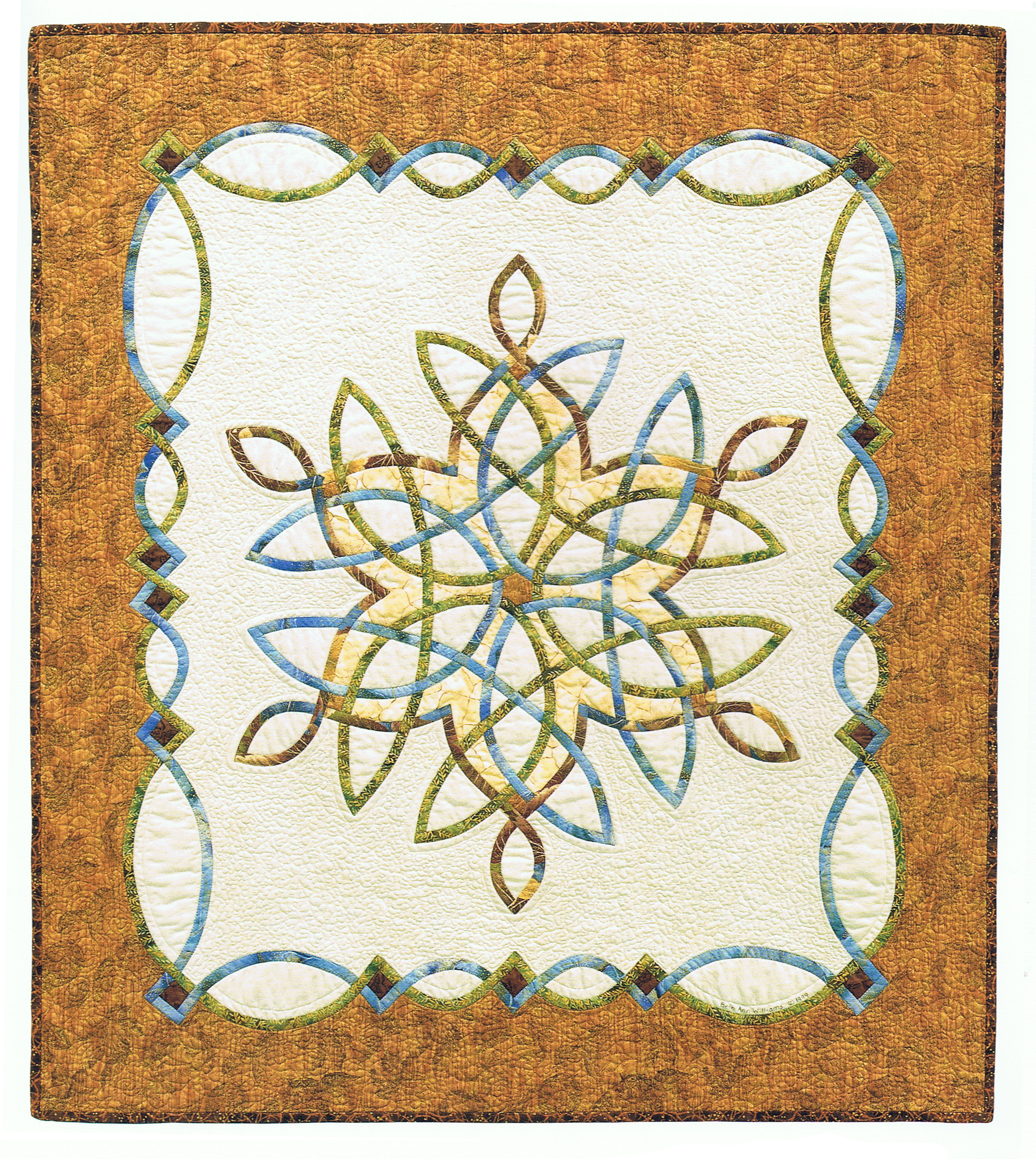

The most complex project in the book is called The Island.

The colors and rhythms of this modern Celtic-style quilt were inspired by a lament attributed to Columcille, also known as St. Columba, a warrior Celt of noble birth who could have been by right a king, but chose to become a monk instead. This very poignant lament was written in the sixth century AD, while he was in exile, and is full longing for the shores of his beloved homeland.

The last quilt I’d like to share with you is included in the gallery section of the book, pattern not included. The background fabric was hand-dyed especially for me by my dear friend Verlyn Verbrugge. It has become a memorial quilt.

It is important to me that Celtic culture not be viewed simply as a “dead” thing – something to be studied, dissected and preserved in museums and folk-parks – but as a living, vibrant expression both of honoring our heritage and embracing our future.

I hope you have, and will continue, to enjoy your journey – wherever it takes you – as much as I have mine.

These are amazing, as are you! Thank you for sharing your work!

Thanks so much, Virginia! I’m a big fan of your work and love the little piece you gave me 🙂

was watching “On Point” and she mentioned your book. I want to make a quilt for my daughter who loves Ireland. My mother’s side of the family was originally from Kilkenny Ireland and I was fortunate enough to visit the area.

I am ordering your book and would like any other helpful information you might have to offer regarding the creation of this.

Hi Barbara,

What a wonderful gift for your daughter! I still use the same methods I described in my book – the only real difference is that I now use Roxann’s Glue Baste It or other water-soluble fabric glue instead of Steam-a-Seam2 when “basting” the tubes in preparation for sewing.

Good luck & best wishes always,

Beth Ann