2025 UPDATE: PDF patterns, online classes and FREEBIES can now be found in my online shop.

I no longer have a dedicated FAQ page, so I’m thinking it might be helpful to address frequently asked questions (FAQ) in a series of blog posts. I’ll start with questions related to Celtic-style quiltmaking and my first book, Celtic Quilts: A New Look for Ancient Designs.

Are there any rules about what colors or fabrics you should use for Celtic knotwork?

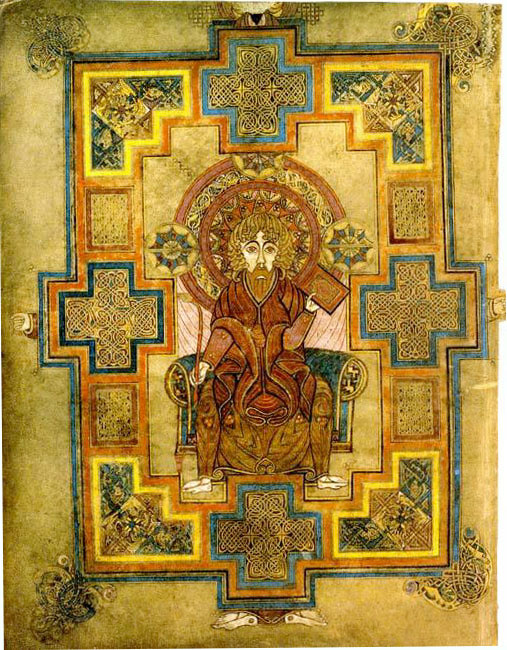

If you look at ancient Celtic manuscripts, you see quite a wide variety of colors being used. In some cases, a given knotwork design is colored in uniformly with the same pigment; in other cases, several colors may be used within the same design. Sometimes the color changes serve to highlight a particular repeating portion of a knotwork design or interlacing border, while other times the color changes seem to have been made at the whim of the scribe. So, there really are no set rules about what colors you can use in a Celtic quilt.

Pick what you like best, or pick a combination that is meaningful to you. Feel free to make choices that please yourself!

I would make sure, however, that there is enough contrast between the color(s) you use for the knotwork and the color you use for the background to allow the knotwork to show up clearly. (HINT: Try overlapping your fabrics and then looking at them from the other side of the room: do the fabrics “moosh” together, or can you still clearly see which is which?)

I would also recommend sticking to 100% cotton fabrics, at least when you are starting out. (You can always get crazy with other fabrics once you are comfortable with the basic techniques.) Quilting-weight cottons tend to be easy to handle and hold a nice crease when pressed. Wash them before using them–but don’t use fabric softener if you plan on using any kind of glue or fusible adhesive to hold the bias tubes in place before sewing them down. The chemicals in some fabric finishes or fabric softeners may impede bonding.

What is the symbolism behind Celtic knotwork? / Do certain designs have specific meanings?

In general terms, Celtic art and design is used to celebrate ethnic identity, sometimes coinciding with national political aspirations. It is also often used for the glorification and worship of God, continuing the tradition of the magnificent gospel manuscripts, standing crosses, reliquaries, and liturgical vessels of over a thousand years ago, or to connect with pre-Christian traditions of spirituality.

In specific terms, Celtic knotwork designs are often assumed to have symbolic significance, a sort of code, as it were, that could be understood if only one had the key. This somewhat romantic viewpoint does not seem to be borne out in reality. However, there is still a great deal of controversy surrounding this question.

Modern suggestions/speculations include the following:

- The intricately intertwining unbroken lines in Celtic knotwork symbolize both the pagan cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, and Christian concepts such as the unending qualities of God’s love and mercy towards us and the eternal nature of the soul. The “endless knot” symbolically ties our souls to the world, or paradoxically, to God.

- Certain types of crosses, whether overt or hidden within knotwork designs, have pagan antecedents in the world-axis and solar (whether circular or spiral) symbolism prevalent in pre-Christian Europe. Others developed from the later Latin cross, or the earlier Chi-Rho symbol, a monogram for the name of Christ consisting of the first two letters of the name of Christ in Greek, overlaid onto each other to resemble a wheeled cross.

- A sense of motion, or the turning of the cosmic wheel, is a characteristic of much of Celtic art.

- Numbers are thought to have possible significance in the context of specific Celtic knotwork designs. For example:

- three – the most sacred number. Powerful goddesses often came in three guises (such as maiden, mother, crone); so does the Christian Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Past, Present, Future and Faith, Hope, Love can also be associated with the number three.

- four – the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, west), four elements (earth, air, fire, water), four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John), or four arms of the cross.

- five – a symbol of totality, with the center representing a fifth direction of space; may also refer to the number of Christ’s wounds.

- seven – cosmic and spiritual order, or completion of a natural cycle; in Biblical terms, it is regarded as the number of perfection

In summary, a few knots do seem to have specific names and/or meanings attached to them (at least in the present time), but generally speaking, most of them do not. And even those that are generally recognized today by a given name (such as the True Lovers Knot) seem to vary in appearance and usage over time.

Are there any knotwork designs uniquely associated with specific Celtic countries?

No, I am not aware of any Celtic knotwork or interlace design being associated more with one Celtic people group than with any other. I’ll try to spare everyone a long history lesson, but here is a short version:

If you go back far enough, Celtic peoples actually stretched all the way from Spain and Portugal to Asia Minor. Over the millennia, invasions & migrations eventually forced them into what is now known as the “Celtic Fringe” countries of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Isle of Man, Cornwall in England, Brittany in France, and Galicia in Spain.

Knotwork and interlace do not appear in the earliest known art/culture of peoples identified as “Celtic.” What is now recognized as Celtic-style knotwork and interlace arose centuries later through a combination of early Celtic design, Germanic animal interlace, and Mediterranean influences brought by Christianity. From about the 5th or 6th century C.E. onward (peaking between 700 and 900 C.E.); we begin to find fabulous examples of Celtic design (including knotwork and interlace) ornamenting gospel manuscripts, carved into stone slabs or crosses, and in ornate metalwork such as jewelry, book covers, and reliquaries.

Through both trading ventures and missionary activity, many of these artifacts (and associated design vocabulary) found their way not only throughout Celtic territories, and but also throughout much of the known world. By the 8th century, knotwork and interlace had become a defining characteristic of Celtic art, and continues to be to this day.

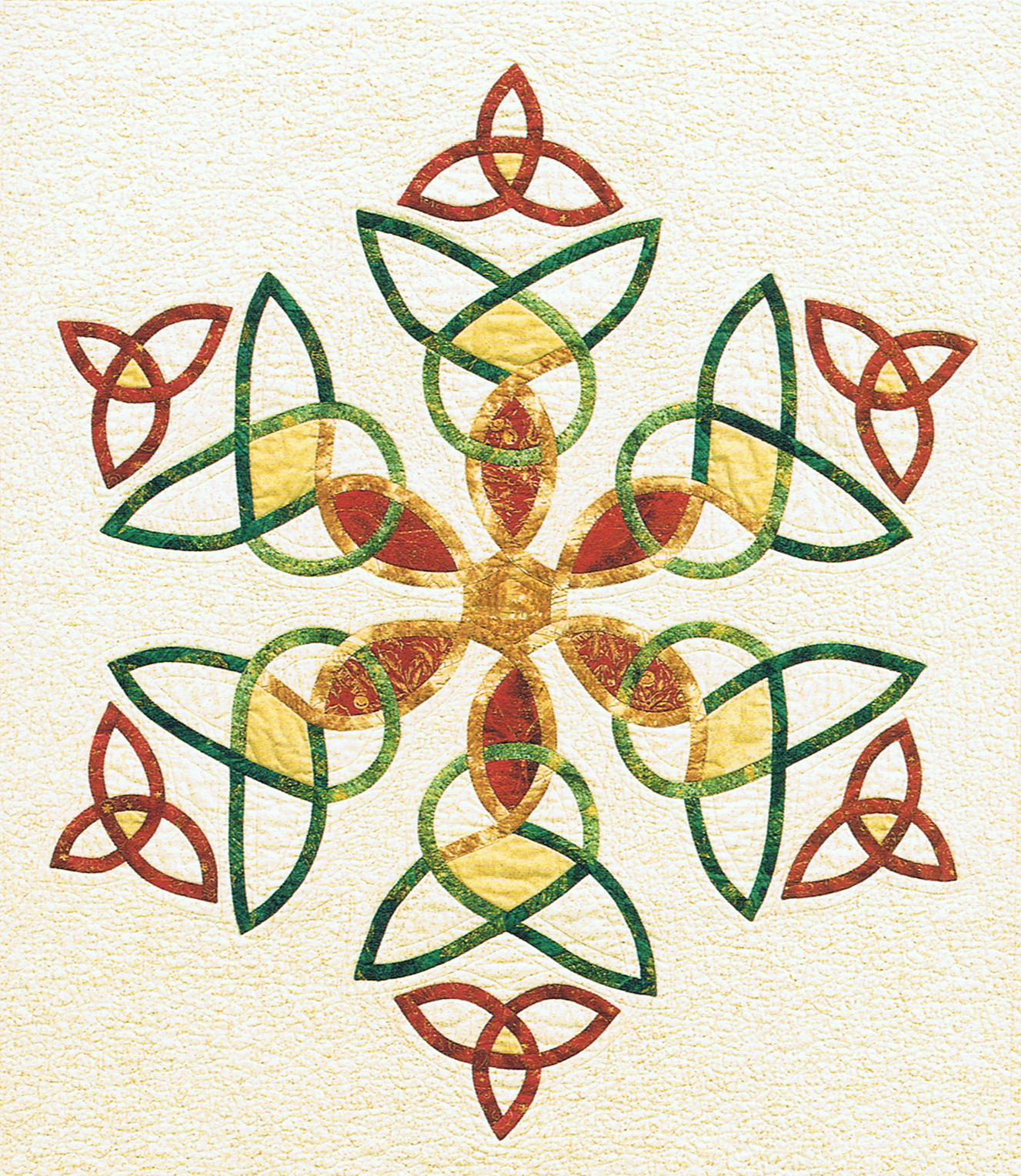

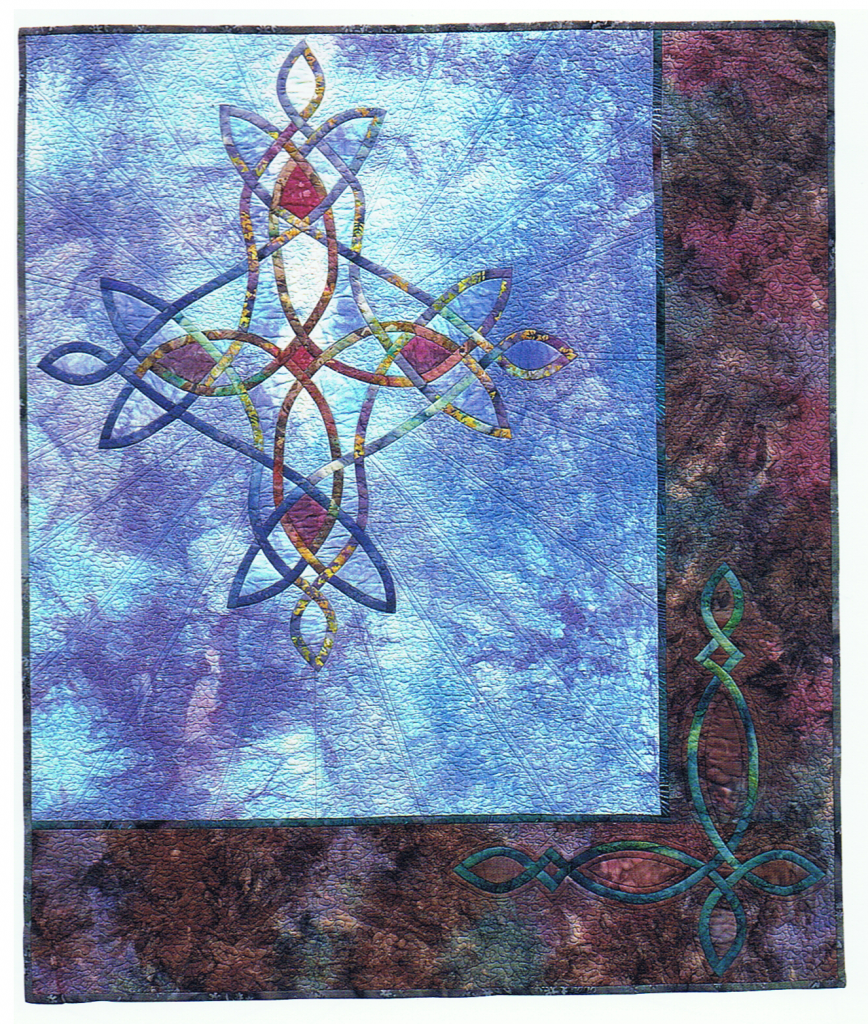

In both my original Celtic-style designs as well as in my interpretations of historical patterns, I’ve remained true to three characteristics of “classic” Celtic knotwork and interlace.

- All lines are continuous, having neither beginning nor end.

- All lines cross each other in an alternating under-over-under pattern.

- No more than two lines cross at any given point.

This pattern was designed by Beth Ann Williams and was taken from her book Celtic Quilts .

Yes it was – that would be me 🙂